%20-%20L%20to%20R%20-%20Tony%20Broderick%2c%20Georgia%20Bruton%2c%20Mat%20Baxter%2c%20Bianca%20Mundy%2c%20Anne%20Parsons-%20Landing%20Page.jpg?width=2000&height=1124&name=QMS%20at%20SXSW%20Sydney%202025%20(3)%20-%20L%20to%20R%20-%20Tony%20Broderick%2c%20Georgia%20Bruton%2c%20Mat%20Baxter%2c%20Bianca%20Mundy%2c%20Anne%20Parsons-%20Landing%20Page.jpg)

SXSW SYDNEY® 2025 INSIGHTS

We hope you enjoyed exploring our newly expanded premium DOOH network and seeing first hand how our assets reach 92% of Sydney audiences every week.

To help with your future DOOH campaign planning and buying, and to give you deeper insights into everything you explored during the tour, we’ve put together a Digital Site Card Pack with key details on each of our new Sydney sites.

What You’ll Gain:

- A deep dive into the key considerations for Digital OOH success

- Expert insights into activating data-led and creative strategies

- A tailored session to explore how this framework can elevate your brand

Enduring Brands, The End Of The Free Internet

and the Music Industry Vs. AI

We absolutely loved our time at SXSW Sydney 2025 this year. But even we didn’t have the time to take it all in. So, this year, we teamed up with our friends at SKMG who got to take in some the sessions and share what they discovered along the way. This is the third article from our shared content series, written by SKMG General Manager, Sam Somers.

The only reason Apple can charge more for exactly the same product as a generic is because it’s an Apple product. Brands create margin extraction.” Mat Baxter didn’t hold back when on stage during today’s full-house QMS session: Great Minds, Greater Brands: The Global Marketing Face-Off That Decodes The Future Of Enduring Brands. Presented by industry legend and QMS Global Advisor, Anne Parsons, the session also featured a panel of some of Australia’s most influential marketers including Tony Broderick, Director of Marketing ANZ for Netflix; Georgia Bruton, Chief Marketing Officer of Brown Brothers Family Wine Group; Bianca Mundy, Head of Brand and Media at Coles; and Mat Baxter, Founder and CEO of Skingraphica.

See, the reason people line up for the iPhone 17 instead of a functionally identical model from anywhere else isn’t because of the hardware, but because of the story. As Baxter put it: “If you believe in brands, you have to believe in nurturing them. They’re like trees. The fruit is what people buy, but if you stop watering the tree, eventually there’s no fruit left.”

While it’s a lazy metaphor – by his own admission – it’s one that sticks, especially in an industry obsessed with quarterly returns and lower-funnel data. Too many marketers, he argued, are hooked on the “performance drug”, that is, short-term activations that deliver quick wins at the cost of long-term health. And when the brand stops carrying the weight, your ability to extract profit collapses. It’s why Nike’s returning to brand building after years of over-indexing on conversion. Why streaming platforms are investing in fandom, not just sign-ups. And why, despite the obsession with omnichannel everything, the focus can be braver than fragmentation. “Omnichannel planning isn’t always right-channel planning,” he noted. “Sometimes the best media plan is one that chooses a lane and commits to it.”

As marketers talk about AI, measurement and efficiency, this panel reminded us of the one thing that doesn’t change: the need to keep watering the damn tree.

Enough with the metaphors.

See, the reason people line up for the iPhone 17 instead of a functionally identical model from anywhere else isn’t because of the hardware, but because of the story. As Baxter put it: “If you believe in brands, you have to believe in nurturing them. They’re like trees. The fruit is what people buy, but if you stop watering the tree, eventually there’s no fruit left.”

While it’s a lazy metaphor – by his own admission – it’s one that sticks, especially in an industry obsessed with quarterly returns and lower-funnel data. Too many marketers, he argued, are hooked on the “performance drug”, that is, short-term activations that deliver quick wins at the cost of long-term health. And when the brand stops carrying the weight, your ability to extract profit collapses. It’s why Nike’s returning to brand building after years of over-indexing on conversion. Why streaming platforms are investing in fandom, not just sign-ups. And why, despite the obsession with omnichannel everything, the focus can be braver than fragmentation. “Omnichannel planning isn’t always right-channel planning,” he noted. “Sometimes the best media plan is one that chooses a lane and commits to it.”

As marketers talk about AI, measurement and efficiency, this panel reminded us of the one thing that doesn’t change: the need to keep watering the damn tree.

Enough with the metaphors.

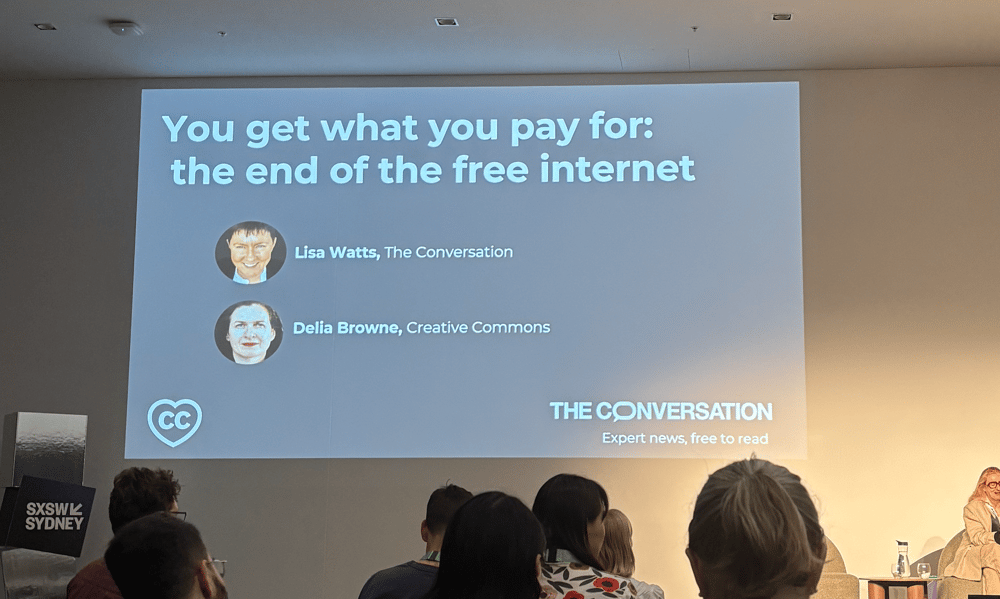

Day two at SXSW Sydney saw us try to wrap our heads around the quiet irony in attending a session about the “end of the free internet” with The Conversation’s Lisa Watts and former Creative Commons Chair Delia Browne telling us about how the internet as we know it is breaking down.

When Tim Berners-Lee built the web, it was designed as a shared commons. You put something in, someone else built on it, and that cycle of mutual benefit created what we now think of as “the internet”. But as Browne explained, that social contract has eroded. “What we have now is just taking,” she said. “The commons depends on reciprocity, and that’s disappearing.” AI is the biggest stress test yet for that idea. The same open data that powered creativity for decades is now being mined, scraped and resold. And often without consent, attribution, awareness. You name it.

Browne put it best: “Things that were available under open license are being taken for free and sold back to us.” The very principle that once made the web thrive (openness) is now being used against its creators.

That should sound familiar. We’ve spent years celebrating “free reach” and “UGC” without always asking who benefits most. What happens when the open internet, the ecosystem that made virality possible, stops being open? When algorithms decide what’s worth seeing or saying? Creative Commons have since put forward a new “signals” framework that offers one possible path forward. It’s an early prototype that lets creators attach conditions to how their work is used in AI training: credit, compensation, contribution, openness. Or as Browne described it: “It’s about giving machines manners.”

It’s easy to see the marketing relevance here. Brands will soon face similar expectations: to use creative and cultural data responsibly, to cite their sources and to respect creative provenance. Just because something’s online doesn’t mean it’s free, and just because AI can do it doesn’t mean it should. If the next internet is built on stolen creativity, the real cost won’t just be paid by artists. It’ll be paid by anyone who communicates for a living.

Nowhere was this tension more urgent than in AI Is Here to Stay, So How Do Artists Stay Ahead? Moderator Poppy Reed opened with the numbers: 40,000 AI music tools on the market, growing by 1,000 every month. By 2028, AI could erase over a quarter of music creators’ revenue. The toothpaste, as she put it, is out of the tube.

CEO of ARIA and PPCA (and SKMG client!), Annabelle Herd, has spent her entire career navigating copyright and digital disruption. Her position was unambiguous: “At its simplest, just do it legally. What they’re doing is illegal. Black and white. They’ve created this false sense of uncertainty.” She pointed to companies like OpenAI’s Sora, which recently launched with background music that sounded suspiciously like copyrighted tracks, deepfakes of Tupac and Rick Astley included. When asked about AI artist Sonia Monet, who was recently signed to a multi-million-dollar record deal after being created using the Suno model, Annabelle didn’t mince words: “That therefore is theft. A product and derivative of theft.”

Meng Ru Kuok, CEO of BandLab Technologies, came at it from a different angle but landed in the same place. BandLab has 100 million users creating 40 million songs a month, most with nothing but a phone and headphones. For Meng, this wasn’t about morality: “Theft is not a long-term business model. If you don’t create a future for your customers, you have no customers.”

BandLab’s built tools like Voice Cleaner, which uses AI to improve recordings from cheap microphones so artists without studio access can compete. The difference? Licensed data. Creator consent. “What we’re protecting is the people who haven’t had their start yet,” Meng explained. “The person that really suffers when the music industry is destroyed is the person who hasn’t had that chance.”

Both speakers demolished the library analogy AI companies love to deploy. The argument goes like this: what’s the difference between an AI model reading copyrighted work and you reading a book from the library, absorbing it, and creating something new? Sounds reasonable until you remember, as Meng pointed out, that someone bought that book. Someone licensed it. Someone donated it. There’s a commercial model already in place. “If you go to a library and take a book out, someone paid for those books. Who printed those books? Someone licensed it, someone published it.” The library didn’t just help itself. Annabelle went further with the gallery analogy: “I walk into a gallery and look at a painting. I can’t then go outside and reproduce every single painting instantly, perfectly.” And even then, she would have paid a fee to enter that gallery.

The conversation turned to what comes next. Annabelle believes the 50+ copyright cases currently in US courts will land correctly, and then the industry can move on to actual licensing discussions. Meng was more optimistic still, predicting that once the legal framework is secured, the debate will shift to what creativity actually means when AI is involved. The kind of debates we’ve always had about Auto-Tune or electric guitars. Cultural arguments, not legal ones.

But we’re not there yet. Right now, as Annabelle warned, the question facing society is bigger than music: “How do we know what’s real and what’s not real?” That uncertainty, both speakers suggested, will drive people back to physical media and live experiences. Something tangible. Something human.

For marketers, the lesson lands hard. Intellectual property is what lets brands extract margin in the first place. If the framework that protects creative work collapses, so does the value of everything built on it. As Annabelle said: “Intellectual property is the foundation of all of it. And it will be the foundation of a trusted and commercially successful AI industry.”

When Tim Berners-Lee built the web, it was designed as a shared commons. You put something in, someone else built on it, and that cycle of mutual benefit created what we now think of as “the internet”. But as Browne explained, that social contract has eroded. “What we have now is just taking,” she said. “The commons depends on reciprocity, and that’s disappearing.” AI is the biggest stress test yet for that idea. The same open data that powered creativity for decades is now being mined, scraped and resold. And often without consent, attribution, awareness. You name it.

Browne put it best: “Things that were available under open license are being taken for free and sold back to us.” The very principle that once made the web thrive (openness) is now being used against its creators.

That should sound familiar. We’ve spent years celebrating “free reach” and “UGC” without always asking who benefits most. What happens when the open internet, the ecosystem that made virality possible, stops being open? When algorithms decide what’s worth seeing or saying? Creative Commons have since put forward a new “signals” framework that offers one possible path forward. It’s an early prototype that lets creators attach conditions to how their work is used in AI training: credit, compensation, contribution, openness. Or as Browne described it: “It’s about giving machines manners.”

It’s easy to see the marketing relevance here. Brands will soon face similar expectations: to use creative and cultural data responsibly, to cite their sources and to respect creative provenance. Just because something’s online doesn’t mean it’s free, and just because AI can do it doesn’t mean it should. If the next internet is built on stolen creativity, the real cost won’t just be paid by artists. It’ll be paid by anyone who communicates for a living.

Nowhere was this tension more urgent than in AI Is Here to Stay, So How Do Artists Stay Ahead? Moderator Poppy Reed opened with the numbers: 40,000 AI music tools on the market, growing by 1,000 every month. By 2028, AI could erase over a quarter of music creators’ revenue. The toothpaste, as she put it, is out of the tube.

CEO of ARIA and PPCA (and SKMG client!), Annabelle Herd, has spent her entire career navigating copyright and digital disruption. Her position was unambiguous: “At its simplest, just do it legally. What they’re doing is illegal. Black and white. They’ve created this false sense of uncertainty.” She pointed to companies like OpenAI’s Sora, which recently launched with background music that sounded suspiciously like copyrighted tracks, deepfakes of Tupac and Rick Astley included. When asked about AI artist Sonia Monet, who was recently signed to a multi-million-dollar record deal after being created using the Suno model, Annabelle didn’t mince words: “That therefore is theft. A product and derivative of theft.”

Meng Ru Kuok, CEO of BandLab Technologies, came at it from a different angle but landed in the same place. BandLab has 100 million users creating 40 million songs a month, most with nothing but a phone and headphones. For Meng, this wasn’t about morality: “Theft is not a long-term business model. If you don’t create a future for your customers, you have no customers.”

BandLab’s built tools like Voice Cleaner, which uses AI to improve recordings from cheap microphones so artists without studio access can compete. The difference? Licensed data. Creator consent. “What we’re protecting is the people who haven’t had their start yet,” Meng explained. “The person that really suffers when the music industry is destroyed is the person who hasn’t had that chance.”

Both speakers demolished the library analogy AI companies love to deploy. The argument goes like this: what’s the difference between an AI model reading copyrighted work and you reading a book from the library, absorbing it, and creating something new? Sounds reasonable until you remember, as Meng pointed out, that someone bought that book. Someone licensed it. Someone donated it. There’s a commercial model already in place. “If you go to a library and take a book out, someone paid for those books. Who printed those books? Someone licensed it, someone published it.” The library didn’t just help itself. Annabelle went further with the gallery analogy: “I walk into a gallery and look at a painting. I can’t then go outside and reproduce every single painting instantly, perfectly.” And even then, she would have paid a fee to enter that gallery.

The conversation turned to what comes next. Annabelle believes the 50+ copyright cases currently in US courts will land correctly, and then the industry can move on to actual licensing discussions. Meng was more optimistic still, predicting that once the legal framework is secured, the debate will shift to what creativity actually means when AI is involved. The kind of debates we’ve always had about Auto-Tune or electric guitars. Cultural arguments, not legal ones.

But we’re not there yet. Right now, as Annabelle warned, the question facing society is bigger than music: “How do we know what’s real and what’s not real?” That uncertainty, both speakers suggested, will drive people back to physical media and live experiences. Something tangible. Something human.

For marketers, the lesson lands hard. Intellectual property is what lets brands extract margin in the first place. If the framework that protects creative work collapses, so does the value of everything built on it. As Annabelle said: “Intellectual property is the foundation of all of it. And it will be the foundation of a trusted and commercially successful AI industry.”

- Sam Somers: General Manager, SKMG